Week 2: ML Strategy (2)

Error Analysis

Manually examining mistakes that your algorithm is making can give you insights into what to do next (especially if your learning algorithm is not yet at the performance of a human). This process is called error analysis. Let's start with an example.

Carrying out error analysis

Take for example our cat image classifier, and say we obtain 10% error on our test set, much worse than we were hoping to do. Assume further that a colleague notices some of the misclassified examples are actually pictures of dogs. The question becomes, should you try to make your cat classifier do better on dogs?

This is where error analysis is particularly useful. In this example, we might:

- collect ~100 mislabeled dev set examples

- count up how any many dogs

Lets say we find that 5/100 (5%) mislabeled dev set example are dogs. Thus, the best we could hope to do (if we were to completely solve the dog problem) is decrease our error from 10% to 9.5% (a 5% relative drop in error.) We conclude that this is likely not the best use of our time. Sometimes, this is called the ceiling, i.e., the maximum amount of improvement we can expect from some change to our algorithm/dataset.

Suppose instead we find 50/500 (50%) mislabeled dev set examples are dogs. Thus, if we solve the dog problem, we could decrease our error from 10% to 5% (a 50% relative drop in error.) We conclude that solving the dog problem is likely a good use of our time.

Note

Notice the disproportionate 'payoff' here. It may take < 10 min to manually examine 100 examples from our dev set, but the exercise offers major clues as to where to focus our efforts.

Evaluate multiple ideas in parallel

Lets, continue with our cat detection example. Sometimes we might want to evaluate multiple ideas in parallel. For example, say we have the following ideas:

- fix pictures of dogs being recognized as cats

- fix great cats (lions, panthers, etc..) being misrecognized

- improve performance on blurry images

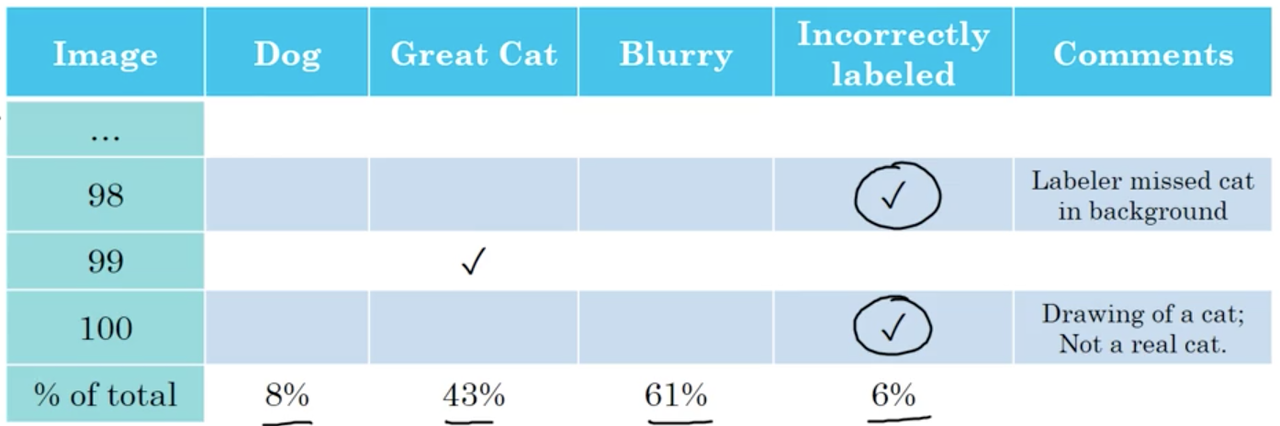

What can do is create a table, where the rows represent the images we plan on evaluating manually, and the columns represent the categorizes we think the algorithm may be misrecognizing. It is also helpful to add comments describing the the misclassified example.

As you are part-way through this process, you may also notice another common category of mistake, which you can add to this manual evaluation and repeat.

The conclusion of this process is estimates for:

- which errors we should direct our attention to solving

- how much we should expect performance to improve if reduce the number of errors in each category

Summary

To summarize: when carrying out error analysis, you should find a set of mislabeled examples and look at these examples for false positives and false negatives. Counting up the number of errors that fall into various different categories will often this will help you prioritize, or give you inspiration for new directions to go in for improving your algorithm.

Three numbers to keep your eye on

- Overall dev set error

- Errors due to cause of interest / Overall dev set error

- Error due to other causes / Overall dev set error

If the errors due to other causes >> errors due to cause of interest, it will likely be more productive to ignore our cause of interest for the time being and seek another source of error we can try to minimize.

Note

In this case, cause of interest is just our idea for improving our leaning algorithm, e.g., fix pictures of dogs being recognized as cats

Cleaning up incorrectly labeled data

In supervised learning, we (typically) have hand-labeled training data. What if we realize that some examples are incorrectly labeled? First, lets consider our training set.

Note

In an effort to be less ambiguous, we use mislabeled when we are referring to examples the ML algo labeled incorrectly and incorrectly labeled when we are referring to examples in the training data set with the wrong label.

Training set

Deep learning algorithms are quite robust to random errors in the training set. If the errors are reasonably random and the dataset is big enough (i.e., the errors make up only a tiny proportion of all examples) performance of our algorithm is unlikely to be affected.

Systematic errors are much more of a problem. Taking as example our cat classifier again, if labelers mistakingly label all white dogs as cats, this will dramatically impact performance of our classifier, which is likely to labels white dogs as cats with high degree of confidence.

Dev/test set

If you suspect that there are many incorrectly labeled examples in your dev or test set, you can add another column to your error analysis table where you track these incorrectly labeled examples. Depending on the total percentage of these examples, you can decide if it is worth the time to go through and correct all incorrectly labeled examples in your dev or test set.

There are some special considerations when correcting incorrect dev/test set examples, namely:

- apply the same process to your dev and test sets to make sure they continue to come from the same distribution

- considering examining examples your algorithm got right as well as ones it got wrong

- train and dev/test data may now come from different distributions --- this is not necessarily a problem

Build quickly, then iterate

If you are working on a brand new ML system, it is recommended to build quickly, then iterate. For many problems, there are often tens or hundreds of directions we could reasonably choose to go in.

Building a system quickly breaks down to the following tasks:

- set up a dev/test set and metric

- build the initial system quickly and deploy

- use bias/variance analysis & error analysis to prioritize next steps

A lot of value in this approach lies in the fact that we can quickly build insight to our problem.

Note

Note that this advice applies less when we have significant expertise in a given area and/or there is a significant body of academic work for the same or a very similar task (i.e., face recognition).

Mismatched training and dev/test set

Deep learning algorithms are extremely data hungry. Because of this, some teams are tempted into shoving as much information into their training sets as possible. However, this poses a problem when the data sources do not come from the same distributions.

Lets illustrate this again with an example. Take our cat classifier. Say we have ~10,000 images from a mobile app, and these are the images (or type of images) we hope to do well on. Assume as well that we have ~200,000 images from webpages, which have a slightly different underlying distribution than the mobile app images (say, for example, that they are generally higher quality.) How do we combine these data sets?

Option 1

We could take the all datasets, combine them, and shuffle them randomly into train/dev/test sets. However, this poses the obvious problem that many of the examples in our dev set (~95% of them) will be from the webpage dataset. We are effectively tuning our algorithm to a distribution that is slightly different than our target distribution --- data from the mobile app.

Option 2

The second, recommended option, is to comprise the dev/test sets of images entirely from the target (i.e., mobile data) distribution. The advantage, is that we are now "aiming the target" in the right place, i.e., the distribution we hope to perform well on. The disadvantage of course, is that the training set comes from a different distribution than our target (dev/test) sets. However, this method is still superior to option 1, and we will discuss laters further ways of dealing with this difference in distributions.

Note

Note, we can still include examples from the distribution we care about in our training set, assuming we have enough data from this distribution.

Bias and Variance with mismatched data distributions

Estimating the bias and variance of your learning algorithm can really help you prioritize what to work on next. The way you analyze bias and variance changes when your training set comes from a different distribution than your dev and test sets. Let's see how.

Let's keep using our cat classification example and let's say humans get near perfect performance on this. So, Bayes error, or Bayes optimal error, we know is nearly 0% on this problem. Assume further:

- training error: 1%

- dev error: 10%

If your dev data came from the same distribution as your training set, you would say that you have a large variance problem, i.e., your algorithm is not generalizing well from the training set to the dev set. But in the setting where your training data and your dev data comes from a different distribution, you can no longer safely draw this conclusion. If the training and dev data come from different underlying distributions, then by comparing the training set to the dev set we are actually observing two different changes at the same time:

- The algorithm saw the training data. It did not see the dev data

- The data do not come from the same underlying distribution

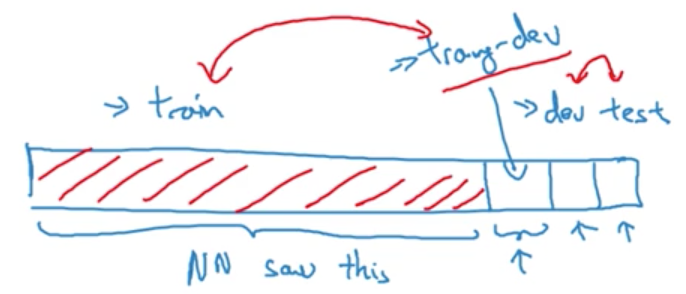

In order to tease out these which of these is conributing to the drop in perfromsnce from our train to dev set, it will be useful to define a new piece of data which we'll call the training-dev set: a new subset of data with the same distribution as the training set, but not used for training.

Heres what we mean, previously we had train/dev/test sets. What we are going to do instead is randomly shuffle the training set and carve out a part of this shuffled set to be the training-dev.

Note

Just as the dev/test sets have the same distribution, the train-dev set and train set have the same distribution.

Now, say we have the following errors:

- training error: 1%

- train-dev error: 9%

- dev error: 10%

We see that training error \(\lt \lt\) train-dev error \(\approx\) dev error. Because the train and train-dev sets come from the same underlying distribution, we can safely conclude that the large increase in error from the train set to the dev set is due to variance (i.e., our network is not generalizing well)

Lets look at a counter example. Say we have the following errors:

- training error: 1%

- train-dev error: 1.5%

- dev error: 10%

This is much more likely to be a data mismatch problem. Specifically, the algorithm is performing extremely well on the train and train-dev sets, but poorly on the dev set, hinting that the train/train-dev sets likely come from different underlying distributions than the dev set.

Finally, one last example. Say we have the following errors:

- Bayes error: \(\approx\) 0%

- training error: 10%

- train-dev error: 11%

- dev error: 20%

Here, we likely have two problems. First, we notice an avoidable bias problem, suggested by the fact that our training error \(\gt \gt\) Bayes error. We also have a data mismatch problem, suggested by the fact that our training error \(\approx\) train-dev error by both are \(\lt \lt\) our dev error.

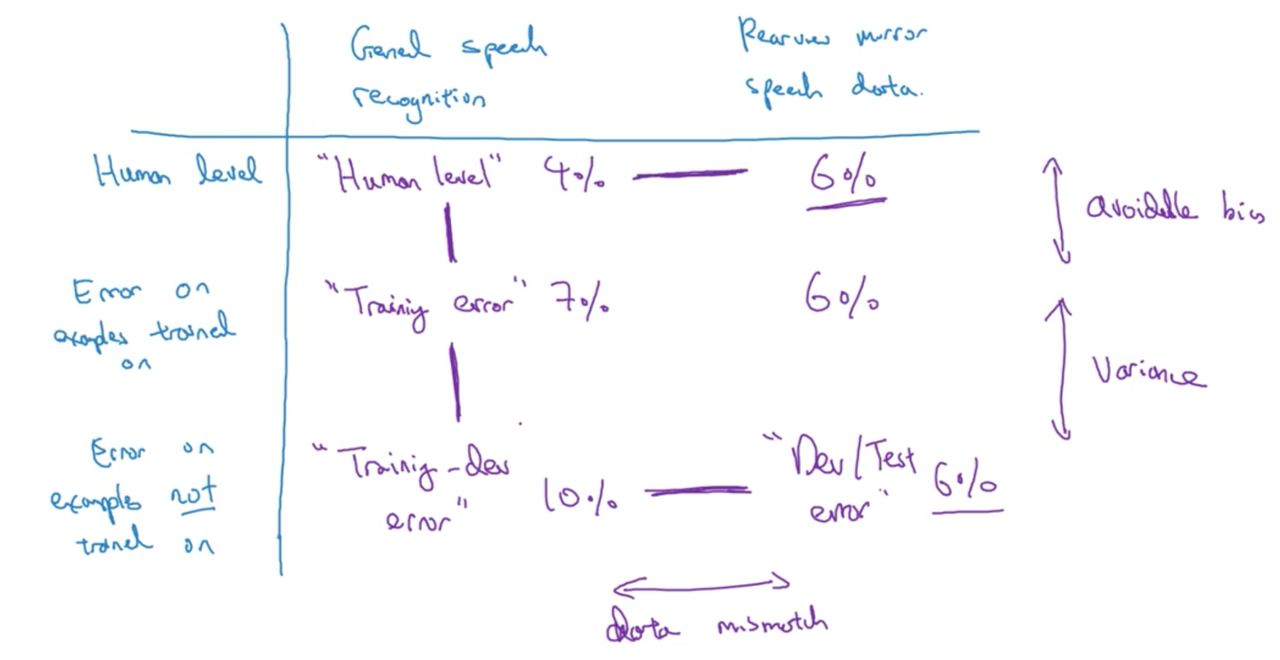

So let's take what we've done and write out the general principles. The key quantities your want to look at are: human-level error (or Bayes error), training set error, training-dev set error and the dev set error.

The differences between these errors give us a sense about the avoidable bias, the variance, and the data mismatch problem. Generally,

- training error \(\gt \gt\) Bayes error: avoidable bias problem

- training error \(\lt \lt\) train-dev error: variance problem

- training error \(\approx\) train-dev error \(\lt \lt\) dev error: data mismatch problem.

More general formation

We can organize these metrics into a table; where the columns are different datasets (if you have more than one) and the rows are the error for examples the algorithm was trained on and examples the algorithm was not trained on.

Addressing data mismatch

If your training set comes from a different distribution, than your dev and test set, and if error analysis shows you that you have a data mismatch problem, what can you do? Unfortunately, there are not (completely) systematic solutions to this, but let's look at some things you could try.

Some recommendations:

- carry out manual error analysis to try to understand different between training and dev/test sets.

- for example, you may find that many of the examples in your dev set are noisy when compared to those in your training set.

- make training data more similar; or collect more data similar to dev/test sets.

- for example, you may simulate noise in the training set

The second point leads us into the idea of artificial data synthesis

Artificial data synthesis

In some cases, we may be able to artificially synthesis data to make up for a lack of real data. For example, we can imagine synthesizing images of cars to supplement a dataset of car images for the task of car recognition in photos.

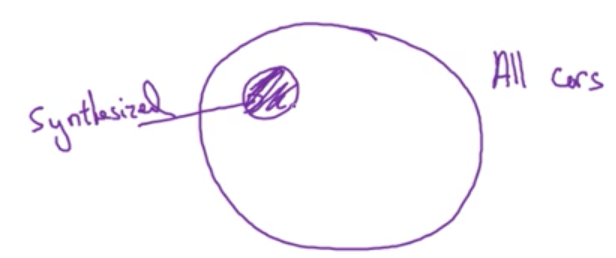

While artificial data synthesis can be a powerful technique for increasing the size of our dataset (and thus the performance of our learning algorithm), we must be wary of overfitting to the synthesized data. Say for example, the set of "all cars" and "synthesized cars" looked as follows:

In this case, we run a real risk of our algorithm overfitting to the synthesized images.

Learning from multiple tasks

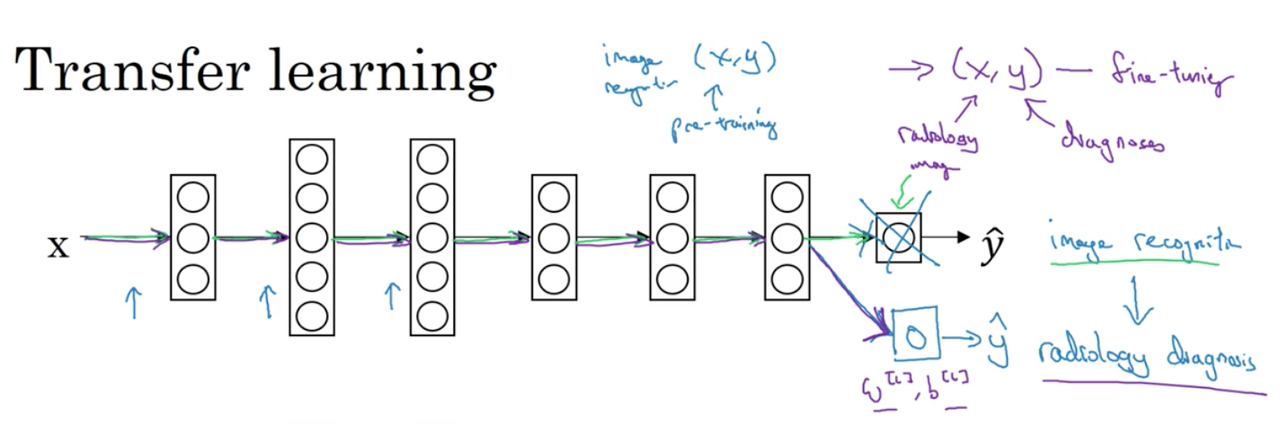

Transfer learning

One of the most powerful ideas in deep learning is that you can take knowledge the neural network has learned from one task and apply that knowledge to a separate task. So for example, maybe you could have the neural network learn to recognize objects like cats and then use parts of that knowledge to help you do a better job reading X-ray scans. This is called transfer learning. Let's take a look.

Lets say you have trained a neural network for image recognition. If you want to take this neural network and transfer it to a different task, say radiology diagnosis, one method would be to delete the last layer, and re-randomly initialize the weights feeding into the output layer.

To be concrete:

- during the first phase of training when you're training on an image recognition task, you train all of the usual parameters for the neural network, all the weights, all the layers

- having trained that neural network, what you now do to implement transfer learning is swap in a new data set \(X,Y\), where now these are radiology images and diagnoses pairs.

- finally, initialize the last layers' weights randomly and retrain the neural network on this new data set.

We have a couple options on how we retrain the dataset.

- If the radiology dataset is small: we should likely "freeze" the transferred layers and only train the output layer.

- If the radiology dataset is large: we should likely train all layers.

Note

Sometimes, we call the process of training on the first dataset pre-training, and the process of training on the second dataset fine-tuning.

The idea is that learning from a very large image data set allows us to transfer some fundamental knowledge for the task of computer vision (i.e., extracting features such as lines/edges, small objects, etc.)

Note

Note that transfer learning is not confined to computer vision examples, recent research has shown much success deploying transfer learning for NLP tasks.

When does transfer learning make sense?

Transfer learning makes sense when you have a lot of data for the problem you're transferring from and usually relatively less data for the problem you're transferring to.

So for our example, let's say you have a million examples for image recognition task. Thats a lot of data to learn low level features or to learn a lot of useful features in the earlier layers in neural network. But for the radiology task, assume we only a hundred examples. So a lot of knowledge you learn from image recognition can be transferred and can really help you get going with radiology recognition even if you don't have enough data to perform well for the radiology diagnosis task.

If you're trying to learn from some Task A and transfer some of the knowledge to some Task B, then transfer learning makes sense when:

- Task A and B have the same input X.

- you have a lot more data for Task A than for Task B --- all this is under the assumption that what you really want to do well on is Task B.

- transfer learning will tend to make more sense if you suspect that low level features from Task A could be helpful for learning Task B.

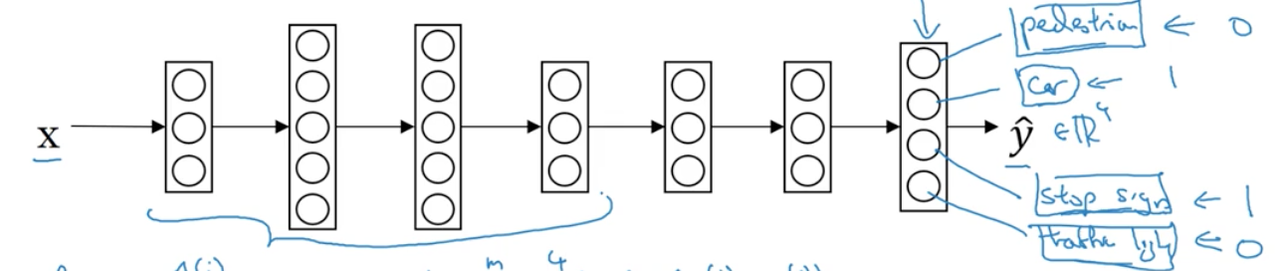

Multi-task learning

Whereas in transfer learning, you have a sequential process where you learn from task A and then transfer that to task B --- in multi-task learning, you start off simultaneously, trying to have one neural network do several things at the same time. The idea is that shared information from each of these tasks improves performance on all tasks. Let's look at an example.

Simplified autonomous driving example

Let's say you're building an autonomous vehicle. Then your self driving car would need to detect several different things such as pedestrians, other cars, stop signs, traffic lights etc.

Our input to the learning algorithm could be a single image, our our label for that example, \(y^{(i)}\) might be a four-dimensional column vector, where \(0\) at position \(j\) represents absence of that object from the image and \(1\) represents presence.

Note

E.g., a \(0\) at the first index of \(y^{(i)}\) might specify absence of a pedestrian in the image.

Our neural network architecture would then involve a single input and output layer. The twist is that the output layer would have \(j\) number of nodes, one per object we want to recognize.

To account for this, our cost function will need to sum over the individual loss functions for each of the objects we wish to recongize:

\[Cost = \frac{1}{m}\sum^m_{i=1}\sum^m_{j=1}\ell(\hat y_j^{(i)}, y_j^{(i)})\]

Note

Were \(\ell\) is our logisitc loss.

Unlike traditional softmax regression, one image can have multiple labels. This, in essense, is multi-task learning, as we are preforming multiple tasks with the same neural network (sets of weights/biases).

When does multi-task learning make sense?

Typically (but with some exceptions) when the following hold:

- Training on a set of tasks that could benefit from having shared lower-level features.

- Amount of data you have for each task is quite similar.

- Can train a big enough neural network to do well on all the tasks

Note

The last point is important. We typically need to "scale-up" the neural network in multi-task learning, as we will need a high variance model to be able to perform well on multiple tasks and typically more data --- as opposed to single tasks.

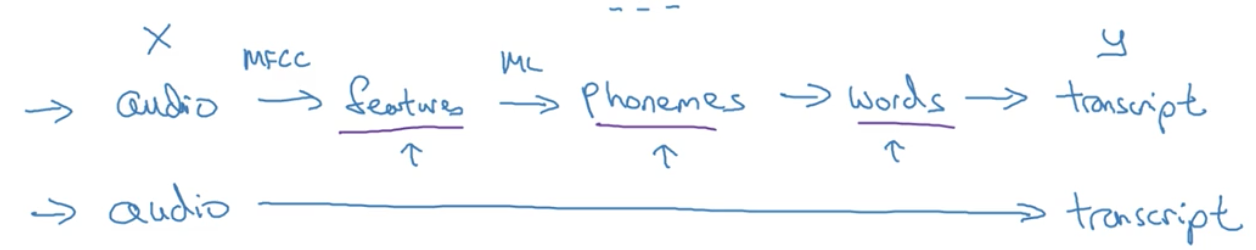

End-to-end deep learning

One of the most exciting recent developments in deep learning has been the rise of end-to-end deep learning. So what is the end-to-end learning? Briefly, there have been some data processing systems, or learning systems that require multiple stages of processing. In contrast, end-to-end deep learning attempts to replace those multiple stages with a single neural network. Let's look at some examples.

What is end-to-end deep learning?

Speech recognition example

At a high level, the task of speech recognition requires receiving as input some audio singles containing spoken words, and mapping that to a transcript containing those words.

Traditionally, speech recognition involved many stages of processing:

- First, you would extract "hand-designed" features from the audio clip

- Feed these features into a ML algorithm which would extract phonemes

- Concatenate these phonemes to form words and then transcripts

In contrast to this step-by-step pipeline, end-to-end deep learning seeks to model all these tasks with a single network given a set of inputs.

The more traditional, hand-crafted approach tends to outperform the end-to-end approach when our dataset is small, but this relationship flips as the dataset grows larger. Indeed, one of the biggest barriers to using end-to-end deep learning approaches is that large datasets which map our input to our final downstream task are rare.

Note

Think about this for a second and it makes perfect sense, its only recently in the era of deep learning that datasets have begun to map inputs to downstream outputs, skipping many of the intermediate levels of representation (images \(\Rightarrow\) labels, audio clips \(\Rightarrow\) transcripts.)

One example where end-to-end deep learning currently works very well is machine translation (massive, parallel corpuses have made end-to-end solutions feasible.)

Summary

When end-to-end deep learning works, it can work really well and can simplify the system, removing the need to build many hand-designed individual components. But it's also not panacea, it doesn't always work.

Whether or not to use end-to-end learning

Let's say in building a machine learning system you're trying to decide whether or not to use an end-to-end approach. Let's take a look at some of the pros and cons of end-to-end deep learning so that you can come away with some guidelines on whether or not an end-to-end approach seems promising for your application.

Pros and cons of end-to-end deep learning

Pros:

- let the data speak: if you have enough labeled data, your network (given that it is large enough) should be able to a mapping from \(x \rightarrow y\), with out having to rely on a humans preconceived notions or forcing the model to use some representation of the relationship between inputs an outputs.

- less hand-designing of components needed: end-to-end deep learning seeks to model the entire task with a single learning algorithm, which typically involves little in the way of hand-designing components.

Cons:

- likely need a large amount of data for end-to-end learning to work well

- excludes potentially useful hand-designed components: if we have only a small training set, our learning algorithm likely does not have enough examples to learn representations that perform well. Although deep learning practitioners often speak despairingly about hand-crafted features or components, they allow us to inject priors into our model, which is particularly useful when we do not have a lot of labeled data.

Note

Note: hand-designed components and features are a double-edged sword. Poorly designed components may actually harm performance of the model by forcing the model to obey incorrect assumptions about the data.

Should I use end-to-end deep learning?

The key question we need to ask ourselves when considering on using end-to-end deep learning is:

Do you have sufficient data to learn a function of the complexity needed to map \(x\) to \(y\)?

Unfortunately, we do not have a formal definition of complexity --- we have to rely on our intuition.